Hello World: The Three (or more) Stages of Learning to Reason

Ever since I got back into reading last year (“studying for the GRE” as I called it), I’ve been meaning to start writing regularly as well. This has been rather tricky for a number of reasons, some of which include (a) finding interesting topics that I can discuss coherently, (b) weighing the pros and cons of the potential outlets (e.g. Facebook, Medium, public blog with/without name, private journal). The latter can easily shape the scope and delivery of the former; for instance, public outlets allow for broader engagement yet their contents are durable, so one may feel pressured to submit polished - and potentially less candid - posts and to steer clear of controversial topics or viewpoints (more on this in a future post). For now, I’ve settled on maintaining a blog on my website. Eventually, I might consider having multiple writing mediums of varying topics and privacy but this seems like a reasonable place to start (we’ll see how this goes!) In this introductory blog post I’d like to touch upon the two following items.

- Reasons why I decided to start writing.

- Thoughts on a general (and still somewhat abstract) approach to processing ideas that derives from my attempts at reading research papers.

I can start by reflecting upon a Facebook post I wrote last September. While in the middle of research deadlines, TA commitments, and graduate school applications, I had a nice day off at SF Comic Con with a friend where we discussed a wide range of interesting topics. After waking up in the middle of the night and pondering for a bit while attempting to sleep, I decided on a whim to write my thoughts out into a rather long-winded Facebook post, focusing on our discussions of Islam and prejudice in the current political climate. The bulk of my post centered around the deliberate conflation of hadiths with the core tenets of Islam for political gain, drawing a brief connection between the world’s major religions and Star Trek:

“…both advocate not the pursuit of material goods but a lifestyle dedicated towards improvements of the self and of society.”

Coalescing my thoughts into an actual piece was an incredibly liberating experience. I loved that it allowed me to creatively and concretely think about an interesting subject and how it introduced some order into my otherwise chaotic internal dialogue (thinking about this as I stumble through the words of this post). I also deeply appreciated the engagement aspect of it, and had nice follow-ups in the subsequent comments and messages. Aspects that could’ve used improvement included better direction and focus, which I anticipated would happen on a first-time attempt at writing a lengthy piece. I feel that, personally, one of my main barriers to writing was circular: it was difficult to write because I hadn’t done so in a while and by lacking either the appropriate medium or self-confidence, I would continue not to write. Getting past this hurdle is the first step. Sustaining it might be challenging but I hopefully I’ll have enough interesting ideas to keep me occupied.

As I start making my way through graduate school, I have yet to master the ability to properly critique a scientific paper nor will I for a while. My first instinct (and the path of least resistance) is always to believe 100% of what the authors say. Perhaps something about the format exudes this sense of objectivity and truth (see this paper for example of format) or maybe it’s because I’ve been conditioned since a young age to treat my textbook as my oracle. With this in mind, the logical next step seemed to be to be highly skeptical about everything, always asking harsh questions and picking apart any visible flaw. This ability, while somewhat useful for the GRE, is necessary but not sufficient for a rigorous and thorough analysis. It was too reactive; I often found myself getting caught up on minute, unimportant details, failing to find broader flaws (e.g. what the authors leave out), and unable to learn the right lessons from papers I dismissed as “flawed”. It’s easy to tear something down and sometimes even easier to trust it on blind faith, but faith and skepticism only gets you so far. From my limited experience, I believe the next step is as follows. You need to creatively and constructively engage with the work by understanding the context in which the authors make their assumptions and then, from your modern and domain-specific vantage point, apply your own reasoning to improve their work.

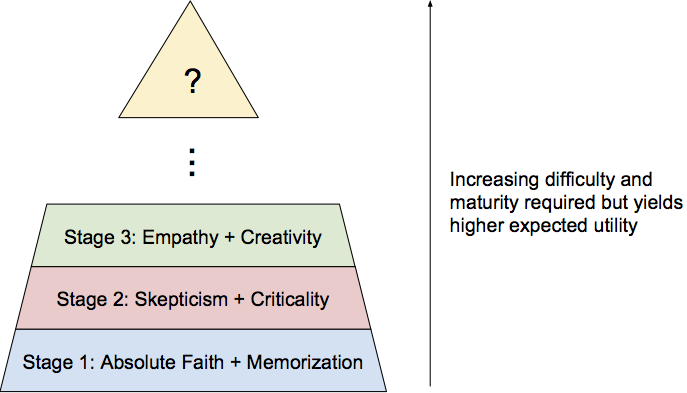

I like to think of this as taking on something of the following form.

I would even argue that reaching the higher stages depend on some aspects of the lower ones. For instance, there’s this general notion that it’s important to learn things intuitively as opposed to using brute force memorization. However, at an elementary level, oftentimes the best way to bootstrap learning is memorize some basics or to take certain assumptions on faith. Only later on you can begin to critique your basic assumptions and draw new, unexplored conclusions. That doesn’t mean you have to take everything on faith. It’s important to ask questions along the way, even naive questions. Sometimes the most naive of questions are the ones that shift the course of an entire field.

More broadly, I believe that this sort of thinking can be applied to the reception and processing of ideas in many contexts. Like scientific papers, ideas aren’t generated in a vacuum. There’s a tremendous amount of context that can get lost in transit and properly understanding and critiquing the ideas of others, especially when communicated in imperfect media (e.g. presentations, writing) and even more imperfect media (e.g. soundbites, 140-character tweets). An audience member with an adversarial mindset might look for any excuse to tear down a presentation, potentially missing the presenter’s point altogether. Unquestioningly ingesting SMS-length tweets from a seemingly reputable source can hamper one’s ability to grasp nuance. In proper scientific inquiry, faith and skepticism are actually quite important; absolute truth does not exist and progress is often made by working within an existing framework of assumptions. But as mentioned previously, these are not sufficient. Science is rarely a lone effort and cannot easily be separated from human society at large. A scientist that understands and capitalizes on this is better equipped to solve problems, but also has a better sense of what problems are worth solving.

So what does writing a blog post have to do with all of this? To even start applying this strategy, I first have to understand my own viewpoints. Writing them down transforms them from fleeting mental processes into concrete ideas. Not all of them are even well-defined so I’ll have to refine them as I go, by sharing them and through engaging with others. As I try to lay down the general foundations for processing and expressing ideas, my hope is that the both the writing and the ideas themselves will improve with time. Of course, I hope it’ll be fun as well.